John C. Jackson of Chagrin Falls, a white guard at Chase Brass and Copper Co., was born in 1905 on a 96-acre farm in Moreland Hills village on the corner of S.O.M. Center Road and Jackson Road, the latter of which was named for his father, Charles W. Jackson. John C. Jackson acquired a number of other farms in eastern Cuyahoga County in the 1930s. He pointed to himself as an exceptional white landowner who did not observe the color line in renting his farmlands.

In 1946, Jackson rented the farm to Burrell Stewart, a construction laborer and farmer, and his wife, and they occupied a remaining small wood-frame cottage on the property. In the next census the Stewarts would comprise one-third of Moreland Hills’ six African Americans out of a village population of more than 1,000. Jackson had rented the farm where the Stewarts occupied a small wood-frame cottage to Black tenants since 1937. At some point in the intervening years, the main farmhouse was reportedly destroyed in a fire, possibly a racially motivated arson attack.

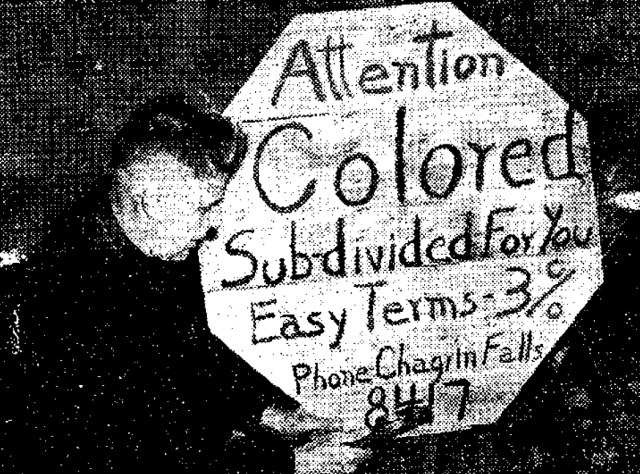

While the Stewarts rented the property, Jackson began to list it for sale and subdivision for Black homebuyers. He noted that he constantly had to replace his for-sale signs because they were repeatedly vandalized, including with red crosses scrawled in spray paint. In September 1948, angry white neighbors filed $175,000 in damage suits against Jackson for daring to try to sell his farm to African Americans, charging that he was doing so as reprisal for not being able to control village politics, threatening their property values in the process. In the suit, one plaintiff also alleged that the Stewarts were running a gambling operation on the premises, a charge that Burrell Stewart vehemently denied, saying he had welcomed only one picnic by a Black organization on the farm, which prompted the Moreland Hills police to warn that picnics were illegal in the village. Stewart dismissed the disgruntled plaintiffs as “dime millionaires.”

The case stirred up emotions across the color line. Ironically, one of the two attorneys who represented the plaintiffs was Harvey Johnson, an African American civil rights lawyer who owned the Breezy-Air Country Club in Northfield. Accepting the case placed Johnson in an uncomfortable position of arguing that people of his race should not be permitted to buy property in areas deemed for whites only. Meanwhile, the situation must have been a source of consternation well beyond Robert Stern because, as the Call & Post reported on October 30, 1948, a mass meeting was held at Orange High School to discuss “handling the problem of Negro neighbors.” After repeated delays, the Cleveland Court of Common Pleas ultimately dismissed the case against Jackson in 1951. Moreland Hills remained almost exclusively white long after the Jackson case receded from memory. As late as 1970, the village counted only five Blacks out of nearly 3,000 residents, and their proportion remained under one percent as late as the 1980s.

Resources

- Aggrey, Rudolph. “Moreland Hills Landowner Defies Neighbors, Hits ‘Dime Millionaires.'” Call & Post. October 2, 1948.

- “Congressman Young Still Trying To Ban Negroes In Moreland Hills Village.” Call & Post. March 5, 1949.

- “Jackson Hopes Negroes Will Build Beautiful Homes in Moreland Hills.” Call & Post. October 9, 1948.

- “Lawyer on Spot in Moreland Hills Real Estate Suit.” Call & Post. October 30, 1948.

- “Letter Box.” Call & Post. December 20, 1947.

- “Moreland Hills Case Dismissed.” Call & Post. May 12, 1951.

- “Moreland Hills Case Postponed While Young Seeks Re-election.” Call & Post. September 16, 1950.

- Simeon, Booker, Jr. “Asks $175,000 Damages In Land Sale to Negroes: White Residents of Moreland Hills Village File Damage Suits Against Neighbor Who Sold Land to Negroes.” Call & Post. October 2, 1948.